I made a full unboxing but haven’t finished editing it yet. In the meantime, here is a quick overview of #based Ping Pong packaging.

masaaki yuasa

Zen Buddhism and Enlightenment in Ping Pong the Animation

I’ve recently been catching myself rewatching the last few episodes of “Ping Pong” over and over again. Although much of the anime is inspired by the 2002 film based on the Ping Pong manga, every frame and shot of the show is made with the complete dedication that only a genius like Masaaki Yuasa could uniquely offer. “Ping Pong” is far from a typical sports anime; it’s a complex story of emotional growth that traces itself through a group of ping pong players. It’s difficult not to scream out in internal joy when we see folks like Kazama and Smile finally becoming enlightened at the end of the show.

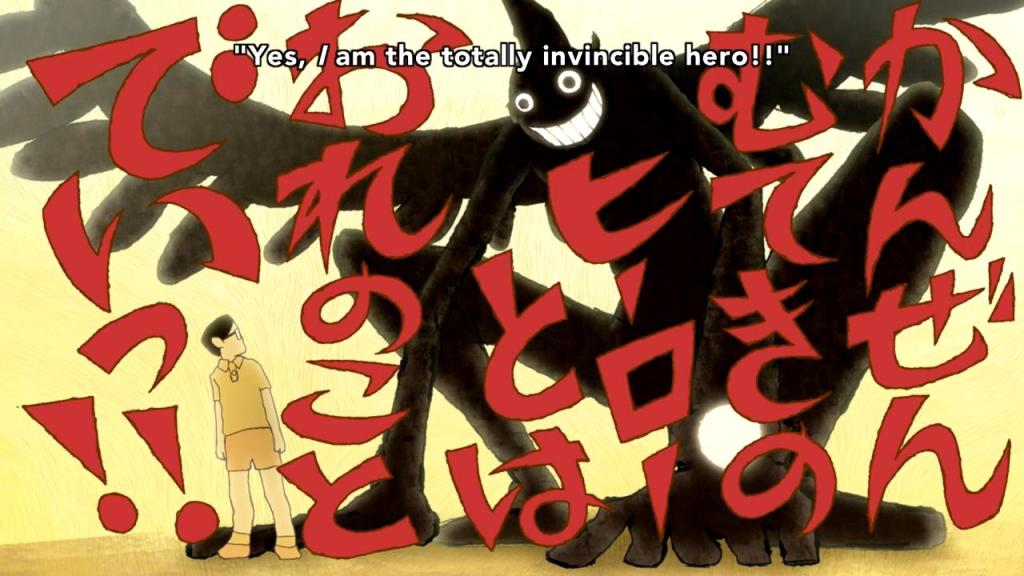

What it means to be a hero – episode 3 of Ping Pong: the Animation

First of all, this episode is amazing. It’s incredibly well-written, very compelling, and it stays true to the philosophical themes established in previous episodes. I talked about the theme of heroism in episodes 1 and 2 of Ping Pong the Animation, and luckily for me, my analysis has only been further validated by episode 3.

A condensed summary of what we learned in episodes 1 and 2 is as follows: Peco and Smile represent two opposing definitions of heroism.

Heroism in Ping Pong: the Animation, episodes 1 and 2

The hero appears!

The hero appears!

The hero appears!

The first episode of Ping Pong deals with the consequences of naive idealism. The episode is probably best summarized with a quotation from Coach: “No man so good, yet another may be as good as he.” The episode is almost entirely centered around Peco as he transitions from being the all-star hero of the show to being exposed as an (apparently) talentless hack. Some contrasts in the narrative are exremely important to note:

1. When Peco dominates the rich boy from out of town, Peco is depicted as a charming hero. The rich boy is shown as ignorant and arrogant, clearly deserving of punishment. When Peco slaps the harshness of reality in the face of the rich boy without even breaking a sweat, he cries out “What were my ten years for?!” — an almost cartoonishly funny exclamation. As the audience, we have almost no sympathy for the rich boy.

2. However, when Peco is himself the victim of Wen’ge’s incredible Ping Pong skills, the narrative takes on a drastically different tone. We see Peco try to assess the situation, trying to calculate Wen’ge’s movements, and even though he loses the first few points, we are under the impression that Peco is just testing the waters; sure, he may lose a few, but the information he’s obtaining will let him triumph over Wen’ge, just as the hero always does, right?

Right?

But no — when Peco attempts to serve a heroic “4,000 year ping pong special”, the ball slips out from underneath the paddle, hitting the wall behind him. It is at this point that both Peco — and we, the audience — realize that the game is utterly out of Peco’s control. No longer can Peco use “science” or “analysis” as a justification for losing points, as we now realize that the game was always in Wen’ge’s clutches to begin with. Wen’ge makes a statement that shocks us to the core: “Your backhand is weak! And your forehand! And your legs! And your reactions! Nothing about you is good enough!” — a statement which completely contrasts with the rosy perception of Peco we had at the beginning, as told by one of the ping pong captains: “Hoshino’s a strong player. He’s goot at footwork, backhand, blocks, everything.”

When Wen’ge skunks Peco, Peco performs a dramatic dive from the top of the screen to the bottom, obviously symbolic of the completely humiliating loss of his heroic status. Peco does not even realize that this is the same fate that he was callously delivering to overconfident rich boys all along. But even so we are led to have sympathy for Peco, because we had rested all of our hopes on his shoulders. Wen’ge is depicted as distinctly unheroic; cocky, cold, and cruel, and not nearly as charming as Peco, and the juxaposition of these two personalities is clearly intentional. With the loss of Peco’s hero-status, our naive expectations of Ping Pong heroism have been completely — and permanently — annihiliated. Ultimately, we learn that the charismatic, gets-what-he-wants hero doesn’t really exist.

The idea of heroism reappears in episode two, but with an interesting twist. When our faithful ping pong coach finally pushes Smile to his farthest limits, Smile finds himself pondering an old childhood memory. Sitting inside a closed locker, Smile waits for a hero to come rescue him, only to hear:

“The hero isn’t coming.”

A robotic arm extends itself to Smile, offering within its hands an alternate solution to a no-show hero. In a cruel and uncaring world, Smile must actualize the results of heroism by himself, and he needs to take action in life, not simply wait unendingly for a hero that will never come.

Smile then presents us with an alternate definition of hero: not a likeable, charismatic personality, but a person capable of superhuman feats — someone who is unquestionably beyond human limitation. Smile imagines himself as a calculating robot, and in so doing, he channels an unbelievable strength and defeats the coach.

Ironically, Smile remembers a quote from his old self: “I want to be just like you, Peco.” Prior to his awakening, Smile had always compared himself to the ideal of classical heroism. But now, Smile realizes that the stoic, logical, and almost cruel “robot” within him is an equally valid definition of hero that opposes classical ideas in almost every sense. Smile therefore transforms himself from an anti-hero, a completely unsympathetic and abnormal character with few redeeming qualities, to a real hero.

(To be updated with the release of episode 3)